Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes (1884-1974), or GRD as he has is known for short, was an authentic dadaist and dissident surrealist whose talents were recognized by his peers, but whose self-effacing manners and prolonged absences from Paris hindered him from attaining the fame of a Tristan Tzara or Georges Bataille. I would be remiss if I didn't take the occasion of the publication in English of his book of plays, The Emperor of China (Wakefield Press; Cambridge, 2015), to express my appreciation for this writer who has given me immense pleasure in reading his stylized French-language novels and poems.

A collection of three plays, the translated book takes its name from “L'Empereur de Chine,” a drama in which the Minister of Peace transforms into the Minister of War then begins hostilities for seemingly no reason. Audiences today would be able to relate to the ensuing decapitations, eviscerations and explosions as much as those who witnessed its first public staging in 1925.

Written in 1916, at the midpoint of what the French historians call the War of 1914-1918, the play opens on a modernist scene conveying a critique of work and power through typists conversing randomly with their supervisor. The emperor's daughter, Princess Onane, is then given the clowns Ironic and Equinox as gifts from a foreign head of state.

With the clowns serving as a chorus, the play moves into the challenging ground of incest between the murderous and suicidal emperor, Espher, the title character, and Onane, who would go on to be killed, along with her unborn child, by her jilted suitor Prince Verdict.

Stemming from a period in which GRD worked out his idiosyncratic anti-philosophy based on gravity, and published in 1921 when Paris dada was at its height, the first appearance in print of the play attracted considerable attention from the press. The shocking final scene depicts Onane's head swinging from a rope as Verdict speaks of life as the shortening arc of an incomplete journey from left to right that comes to rest at the end of a vertical line. Theater critics have called it a masterpiece.

In his excellent translation, Christopher Butterfield renders this soliloquy, in part, as:

Replicating in English the 1966 Éditions Gallimard book of GRD's major theatrical works, the Wakefield Press translation also includes “The Mute Canary” and “The Executioner of Peru.” But rather than think of GRD as a playwright or poet, for me he will always be a novelist, the sane brother of Bataille. As dissident surrealists, they avowedly wrote novels, whereas André Breton was critical of the form. While Bataille is perhaps more transgressive in his novels than GRD, their philosophies seemed to have overlapped given the centrality of gravity for GRD and Bataille's lightness and heaviness of being.

Breton would denounce GRD, as well as others, in the 1929 Second Surrealist Manifesto, describing the revue GRD edited, Bifur, as “remarkable trash,” adding that GRD had followed up the Emperor of China with a “series of odious crime novels.” GRD promptly broke with the leader of the group and later authored a text in which he described Breton as a false friend, hypocrite, sexton, cop and priest. This appeared in a 1930 pamphlet, A Corpse, alongside essays by many others, including Bataille, who wanted to put exclamation points on their ruptures with Breton.

The pleasures I experienced from the GRD novels republished by Éditions Allia—Céleste Ugolin, Smeltering, Adolescene, Monsieur Jean ou l'amour absolu, Clara des jours, and L'Atruche aux yeux clos—prompted a deeper search for GRD, finding him in the bookstore that used to be located between the famous literary cafés on the Boulevard St. Germain and then in more obscure used stores scattered throughout the city, including one in which the proprietor opened a bottle of wine at the mention of GRD.

I looked for more GRD at the national library, both at the opulent downtown Paris Richelieu site and in the more socialist François Mitterand bookcase-shaped buildings to the east of the city. It was there in 2012, across the river from Parc de Bercy, that I was lucky enough to first hear recordings of his “cheerfully cynical” voice and not long afterward, outside the nearby complex of cinemas, to take a photo of Christa Theret, who was playing Renior's model in the then-premiering film about the painter.

GRD, who anonymously worked on the autobiography of the actress Sarah Bernhardt, was himself a scriptwriter of dramatic films, something that he said came quite easily to him—he would have appreciated my coincidental encounter with the actress who smiled as my newly purchased basketball rolled away down the Avenue de France. I'd dropped it absentmindedly to leave my hands free to operate the camera. GRD was friendly with Brassaï, the noted Hungarian photographer, and took him around Paris to find locations for his legendary night shots.

Originally trained as a painter in Paris at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and at the Académie Julian, in 1913 GRD renounced painting and would only later pick up the brush again, painting mechanistic works alongside his dada confrere Francis Picabia. Despite his many minor successes, at several points GRD struggled to live in Paris. After the War of 1939-1945, he moved to the south, to the Alpes-Maritime department, first near the beach town of Juan-le-Pins, before eventually settling in a mountainside village, just a ways inland from the Mediterranean with a vista of Cannes to the West and Nice to the East and the Var River running between them.

I traveled with my Russian muse in 2013 to this dada village of Saint-Jeannet, so-called because, in addition to GRD, the dada “founder” Tzara also lived there for a while. From a mountainside terrace we drank the partially sun-fermented wine, known as vin tuilé, and took in the vista with the island of Corsica in the ultramarine distance. On our way down from the mountain, in the larger town of Vence, on a hunch we got off the bus outside La Galerie Librairie Basse Fontaine.

“Do you have, by chance,” I asked, “any Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes?”

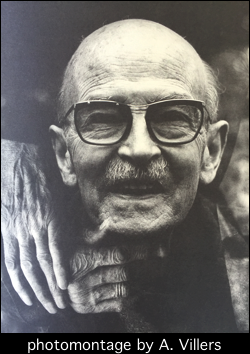

“He's right here,” the patron answered, pointing to a bronze bust of the bald, mustachioed poet, appearing much as he did in photographs taken by his friends, such as Man Ray.

I found myself face to face with GRD. Touching the bronze bust and an ink drawing by him, I knew I would never be so close to GRD as in that Vence bookshop. He died in Saint-Jeannet in 1974, from an age-related illness but in dramatic form—right after a national television broadcast about him in which he turned to the camera at the end of the show while covering his face with a cape and pronouncing in Latin that “the comedy is finished.”

Vence was important for GRD primarily because of his relationship with Jacques Chave, owner of Galerie Chave, where in 1965 there was a major retrospective of GRD's visual art. According to Laure Matarasso, owner of the eponymous bookstore in Nice founded by her father, Jacques, GRD was a modest man—unlike many other dadaists—who was apparently well-liked by nearly everyone who knew him.

In the second volume of his posthumous memoirs, (Mémoires: Rencontres inopinées II; Editions Laure Matarasso, Nice, 2014), Jacques Matarasso writes about lending rare dada books for the 1965 GRD exhibition in Vence and becoming friends with the poet and painter, eating meals prepared by GRD in his home perched on the Saint-Jeannet mountainside. GRD, along with his wife, did much the same with Pablo Picasso at one of the celebrated artist's riviera studios, only for weeks on end. In his history of modern art, GRD vividly depicted the phenomenon via three or four categories—dadaism, surrealism and Picasso, with a quick nod to the “universe of abstraction.”

In 2015 I jokingly told Laure in her rue Longchamp bookstore that I wanted to sign up for the Nice school of surrealism, only to find myself days later standing with her over reading tables as she expertly edited the translation of one of my poems, graciously accommodating my request. These lessons, and those taught by GRD, are from a school that doesn't exist except in my mind and when I'm in the environs of Rue de la Liberté and Boulevard Victor Hugo in Nice, streets that I now favor over those of Paris, or in the waters of Nice's Baie des Anges, with my muse.

The short walk from the Promenade des Anglais across the rocky beach to the foamy shoreline is for us—my surrealist special agent 89 and me—the outset of a mission. I set the bezel on my watch as cool waves lap at our shins and thighs. She shoots me a wink that says in Russian “let's go” as we lower our goggles, leading me with her emerald green eye into the shallow cyan sea that drops off quickly and becomes the liquid blue de France.